Detours / Cause for Alarm / The Syncretic Cinema

Hello and welcome to the first newsletter for Art & Trash! Art & Trash is my series on underground film, but it’s also an umbrella name I give to this side of my work that deals with video essaying and related found footage filmmaking and scholarship. The newsletter will often, but not always, give updates and announcements for Art & Trash, and will also give updates on related things, such as my non-serial video essays and my experimental films and publications.

UPDATE: PLANS FOR 2021

Art & Trash premiered in February 2021 with a twelve-episode first series, featuring episodes on subjects as diverse as Ed Emshwiller, Chester Novell Turner, The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda, and The Telephone Book. Those episodes are all presently up at Art & Trash. The main series will remain on hiatus through the remainder of 2021, launching its second series in early 2022. However, a few episodes for the 2022 season will receive previews this fall in connection with live events, such as the launch of a book I contributed to, Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada, alongside Michael Zryd, edited by Jim Shedden and Barbara Sternberg, which is planned for November. This book also features material that was used in last season’s video essays on Louise Bourque and Josephine Massarella.

In the meantime, I will be ‘broadcasting’ the first season of Detours, a series on the bruised soul of film noir, focusing on the classic period of Hollywood film noir (1941-1958). Taking our name from Edgar G. Ulmer's Detour (1945), one of noir's essential nightmares, we are following in the tracks of his hero, Al Roberts, thumbing a ride straight into the broken heart of postwar American cinema. In film noir, even the pictures lie. The series will run throughout the fall with episodes on Cause for Alarm, The Spiral Staircase, The Window, Edge of Doom, and other less-considered films from the classic period of film noir, starting today. Episodes will appear every Monday for the coming weeks, viewable on the Detours Vimeo channel.

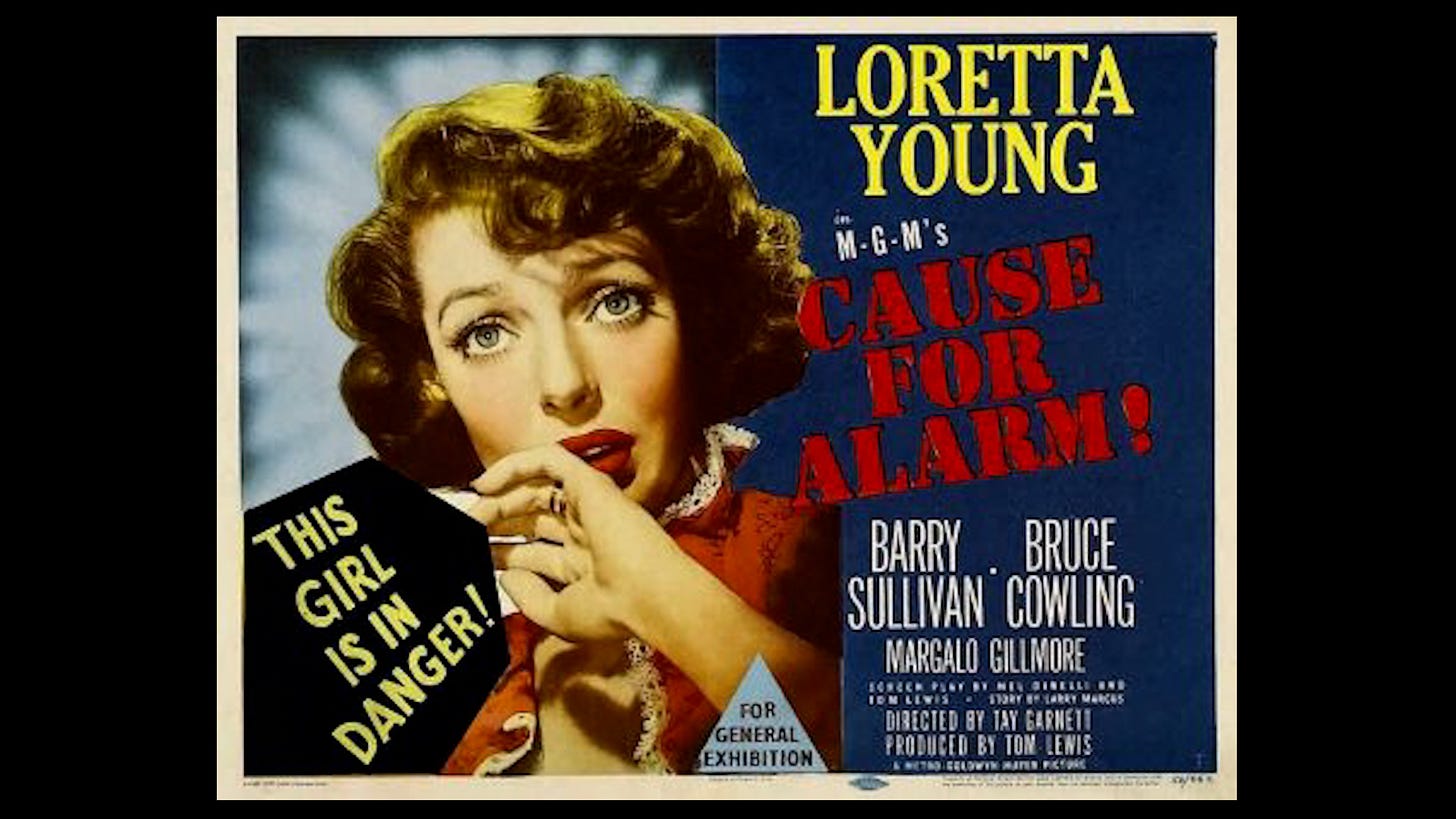

THE BROKEN SHIP: THE WHISPERING VILLAGE IN CAUSE FOR ALARM! (1951)

The first episode of Detours is launching today (September 13) on Vimeo.

The synopsis of the episode:

Cause for Alarm is a sunlit village noir, set in a pastoral home staged with vines as fertile as the town’s paranoia. Through the twentieth century, representations of suburban life have consistently borne the veneer of a false smile, fixed to cover a deep wilting of the American dream. From the thread of loneliness that drives Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, to the beetles in the grass that open David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, there are so many illustrations of the suburbs as a compromised Paradise that it becomes a cliché to say that Mayfield and Maple Street, USA, are not what they appear to be. This video essay contemplates the world of Ellen Jones, a housewife trapped in a suburban panopticon.

I was drawn to Cause for Alarm as a subject for this first episode because it’s a film that I’ve known for a very long time. As a studio film that drifted, out of neglect, into the public domain, Cause for Alarm was a staple on late night movie shows like Off-Beat Cinema, which I watched every week when I was a child. Because of that I had always been under the impression that the movie was ‘bad’, or that it belonged to the family of ‘bad’ movies - which always seemed far more alive to me than ‘good’ movies - that I would see in that setting, films by Roger Corman and Ed Wood. Thinking back I can recall having homemade double bills, taped from television, of pairings like Robot Monster 3D and Cause for Alarm.

But Cause for Alarm is far different than I had remembered it: an accomplished Hollywood melodrama with solid production values and studio distribution, it explores the paranoia of Cold War-era American suburban life, but it also anticipates the style that the television sitcom would soon adopt a similar style in portraying that same environment. The film focuses on a homemaker, Ellen Jones, whose traumatized husband George concocts a murderous conspiracy with himself as a target and his wife and doctor as his adversaries. He writes a letter accusing them, tricks Ellen into sending it, and then, while attempting to kill her, suffers a fatal heart attack. Ellen then spends the remainder of the film trying to regain the letter from her local postman. (Where some critics have found it strange, cynical, or amusing that Ellen Jones immediately becomes focused on self-preservation, I see only a prolonged and desperate act of mourning).

In making this piece, I focused on the ways in which menace could be suggested by the most quotidian details of that world: shadows falling in corners of the Jones den; the sun-soaked lawns and picket fences; lingering shots of Ellen Jones at the sink tending to everyday matters, and later, again at the sink, but contemplating her fate. Cause for Alarm contains such images that resonate with the expressionistic character of noir, however subtly, in contrast to the terrifying cityscape so commonly taken as the paradigmatic world of noir. In The Broken Ship, even as I exaggerate the poetic undercurrent of this imagery through juxtapositions (ex. Ellen looks out of the blinds of her bedroom and I cut to Ellen looking up at the window from outside), I am also interested in the possibility of finding humour even where there is none in the source film. Cause for Alarm is, at times, aware of its gallows humour, but it is also a film that finds an accidental comedy in the garishness of its melodrama. In exploiting this aspect of the film, I was aided by the more bouncing and joyous sections of its score, by André Previn, used in the original context to suggest a whimsy and cheer to the suburbs, but used here to emphasize the inflated expressions of Loretta Young and Barry Sullivan’s performances, a common trait of the Hollywood melodrama.

Cause for Alarm is not a common example of the noir film, but as I argue in this video, it suits the broader ‘family tree’ laid out for noir by Raymond Durgnat early on in the style’s critical reevaluation (1970). And in a world as tranquil as this suburb, we are given cause to doubt appearances. As I observe in the video, so much tranquility suggests its opposite. This video essay uses the plasticity of the image to convey this duality, occasionally transforming the film’s bright compositions into photographic negative, to suggest a shadow world that suits Young’s desperate, bewildered expressions, an effect I can rarely see without thinking of Stan Brakhage’s The Way to Shadow Garden (1954), made three years after Cause for Alarm and also involving a figure whose knowledge of their world is transformed by violence. The Oedipal hero blinds himself, then gropes through a garden radiating darkness, the camera revealing his blood-streaked face among the plants. Ellen Jones also experiences a transformation of vision, albeit a less mythic, more packaged and clichéd transit, stumbling from the halcyon security of the suburb and into the restless and terrifying facts of it.

THE SYNCRETIC CINEMA

This miniature was written to commemorate the fifth anniversary of MUTA, a festival in Lima, Peru that has been a focal point of activity for the international found footage film movement since its first edition in 2017, and which has also created a lot of support for related work, such as video essays. “The Syncretic Cinema” was published in Spanish during their festival earlier this month, and the full catalogue can be found here.

With this piece, I’ve argued on behalf of the particular role that the MUTA festival plays, as a beacon for those seeking a certain kind of experience. At the same time, I have tried to interrogate what drew me to found footage filmmaking in the first place, and what possibilities may lie untapped in its origins.

Found footage filmmaking is the primary syncretic cinema of the twenty-first century. The found footage film can be a declaration of many things: contemporary media literacy that pushes even the recent past into an exaggerated distance; the willingness of our society to force images to tell us discomfiting truths; and a pantheistic faith that takes as its gods the amateurs and its temples the archives. It is the child of information, aesthetics, and faith, born mature, fully formed, into the stitched-up body of the Creature. Such films draw from pre-existing imagery to disrupt our sequential expectations, or to cultivate new conjugations of the moving picture, or to mine the past for the most elusive details. They retrain us in a critical mode even as they hypnotize and cheer and terrify us. They are syncretic because, of all of the forms that the movies have taken, this is the form with the most potential to draw together diverse ideologies, forms, sources, systems. It is the approach that, more than any purely creative filmmaking process, remains capable of communicating totality in this wasteland of images. Its splintering polyphony of root-gestures bring us nearest to the art-to-end-all-art, to the ultimate works of poetry in the west. This cinema has no special debts to the rhetorical traditions of storytelling and often acts to refute those systems. For this refusal, it can use wit. It can use force. It can be deathly serious or bawdily comic. It is an art of absolute possibility.

Whatever name one knows it by—found footage, remix, recycled—this cinema exists in its present varieties because of the common aspiration of diverse techniques. The films that MUTA celebrates are legion in their influences; this is a collision of many parts. Recycled cinema is by its constitution an eclectic joining of past and present. It is a thirteenth-century stone angel carrying a sixteenth-century sundial at Chartres. It can be recognized by the presence, or even coexistence within any given work, of plastic sculpting of the image, of the readymade ‘perfect films’, of essayistic principles. And what is the use of a syncretic cinema that is materially self-conscious, and yet, tethered to those real things that images contain, that receding horizon of history? For audiences, such films offer the possibility of both an edifying experience and an aesthetic spell. And for artists, we are freed to speak in many borrowed voices and through many ages, an ever-expanding archive of passing ages that are not our own.

My contributions to the field of recycled cinema are linked to the activities of MUTA, and have been since 2017 when Milagros Távara Estela approached me about screening Potamkin, my first feature as well as my first attempt at making a long-form found footage film, at the festival’s first edition. For the second edition, the festival commissioned my second feature, Tondal’s Vision, a phantasy of the afterlife. For the third edition, I came in person bringing with me two new films, Resurrection of the Body, in tribute to my late friend John Hofsess, an attempt to cast the impression of his soul; and Phantom Ride, a home movie/road movie hybrid. And for the fourth edition, in the midst of a global pandemic, the Mutantes screened Lulu Faustine, a reckoning with the ghosts of the jazz age and beyond. Across these films, found footage has no uniform meaning, but the specific sources carry with them strong associations of memory and the long shadow of history. These sources include every film seen by a poet who died young; a film made to educate the masses; fragments of the unfinished films and educational videos made by a friend; the voluminous home movies of a man obsessed with filming the landscape by way of the open road; and a stark and terrifying allegory for male obsession and violence. Almost all of these films are collaborations with my father Stuart, whose collage soundtracks mirror my images naturally because of shared aesthetic territory: I’m fortunate to have gained his passion for polyphony. Inheritance is a major theme in these films, which seek to reaffirm the great themes of modernity and to further strain the aesthetic boundaries of difficult modernism, while also repudiating the affluent and prejudicial stations of society that these sources had critiqued, or in some cases, had been produced from. Recycling cinema means wrestling with inheritance and responsibility.

It was during my visit to Lima, in the festival’s third edition, that I recognized how bound my recent activities and the mission of MUTA were. In the programs and activities of the festival I saw this passion for a syncretic cinema formed from all manner of social and aesthetic inquiry. In the workshops and lectures I met an audience that was thirsty, as I am, to face the light of new feelings and new ways of being. Is the found footage film itself, this consequence of a process of films begetting films, in search of utopia, born as it was, in Joseph Cornell’s home on Utopia Parkway in Queens? It commands us to wonder at what exactly is being recovered, resurrected, recycled. Witness, wonder, memory, document, diversion, trivial details. And the glimpse of a nascent maturity for an art of a distant and fading light.