Hi all,

Further to our newsletter: the Art & Trash patreon is hosting Canadian experimental filmmaker David Rimmer’s great and rare documentary Language of the Brush, on painter Jack Wise, streaming until noon tomorrow. It’s free to sign up!

David Rimmer passed away a short time ago. To celebrate his life and his impact on me, I recorded this audio commentary about David’s film Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper. Enjoy!

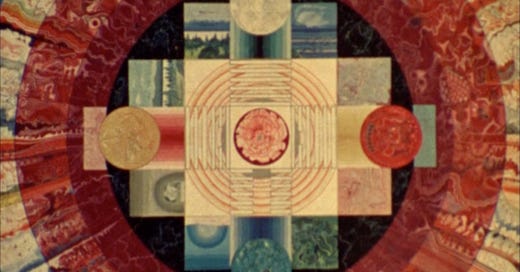

This film was a breakthrough work for Rimmer, whose involvement in filmmaking evolved through the late-1960s from family-of-man phenomenological psychedelia, a quality in Rimmer’s first films that recedes to something more austere and minimalistic, realized in a series of films in 1970, chief among them, Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper. Rimmer’s first films were maximalist in part because of what had influenced him: through the years, Rimmer claimed to have been inspired to make films by a talk that Stan Brakhage gave where Brakhage talked about rediscovering freedom, that you could spit on the lens of a camera and transform vision, that you could think about this medium in totally new ways and break from convention; and in addition to that inspiration, it seems to me beyond doubt that Rimmer was also inspired by the Pacific coast landscape, inevitably maximalist in all the phenomena that the tides took in, and the surrounding culture, with his home of Vancouver a diverse hub, an east and west intersection where one could have a kind of Omnist faith riddled with symbolism from an all-encompassing, borderless spiritual history. Those values aren’t dispensed with when he moves towards minimalism, for we find that this new minimalist turn in his work is not clinical or cold, but full of the curiosity and passion and hunger of an expanding consciousness: Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper witnesses a gradual transformation from an ordinary western record, documentary b-roll gleaned from the trash, to a psychic impression that suggests something distant and mystical, otherworldly. In other works from this same period, Rimmer begins to use repetition and symmetry to re-mystify action: a busy river channel, a dance, falling trees, a crowd of spectators, a day of recreation on the seashore, all become subject to intense, ecstatic meditations. Even as Rimmer became a formidable presence in the developing community of structural filmmaking, he remained a proponent of that west coast Buddhist-Omnist cinema that is a cinema of mystery and romance. The cool patience of minimalism and the warm, tripping passions of Beatnik-cum-hippie glory converge in his formalization of elastic time. That elastic time can be seen here in the restless repetition-and-variation of a single shot, but in other films he will prolong shots, effecting an extreme and probing slow-motion.

The germ of Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper is this scrap of documentary footage, a medium-wide shot of an assembly line worker, a woman, drawing and shaking out a big sheet of cellophane. The cellophane seems to fly towards the viewer, cast up vertically, such that, as the image evolves, it will come to feel like we are being smothered by it, or drowning in it. This loop is near-perfect because it is hard to tell where the cut is in casual observation, harder to tell as the loop begins to overlap and change its textures and tonalities and colour: so it’s hard to see the beginning and end, and is this a tribute to Rimmer’s skill in closing the loop, or to the mechanization of the human body on an assembly line? I say this because it’s easy enough to commend the loop as an inscription of the mechanical movements of modern labour, where bodies become the cogs and gears of a machine. Rimmer found the shot in a scrap pile. It came from a National Film Board of Canada documentary. Rimmer had been involved with Intermedia, which was a foundational Vancouver arts association that served as a platform for artists working across media and in new multimedia forms. Film materials from both the NFB and the CBC would make their way to Intermedia, and artists would draw from those materials to make new work, and that’s how he found this clip, and with it in hand, he began to print the film in all kinds of ways: to make negative and positive versions of it, to print it to colour stock with colour filters, printing it in high contrast—we see all of these approaches bleeding in and out in the final version. At Intermedia happenings, Rimmer would include these loops as projector performances, often in tandem with poetry readings and free jazz and dance performances, as was the nature of such happenings. When he went about cutting it all together as a film, Rimmer was after a specific effect; he would later tell Alex MacKenzie, “the idea was to take this image and just disintegrate it over time. Do as many things that I could to it to see where it would lead.” Rimmer found that the meaning of the image changed: over time, showing the film to audiences, he found his sense of the composition met a welcome challenge from those who saw it as a work of symbolic transformation. For some it was a feminist work—here is woman trapped in monotonous labour, sewing cellophane like the Fates spinning thread—for others it was an Orientalist work, with the worker’s form changing from that of a western labourer into a Hindu God, the icon of a dancing Shiva, in whose grace we witness the panchakritya—creation, preservation, destruction, concealment and salvation.

That verticality that I mentioned earlier is a part of this mysterious invitation, this symbolic transit to another plane, in that the vertical action of shaking out the cellophane gives a sensation of being drowned, as if waves are overtaking both the assembly line worker and the composition itself, and therefore, us. This effect is furthered by Don Druick’s score, of percussive tones that skitter and rumble and reverberate as if occurring across some vast distance, with overlapping rhythms that, like the image, suggest mechanization, at times mirroring the rapid function of the projector’s intermittent mechanism, a rapid function that becomes an essential part of the image when the shot begins to flicker, multiple versions of the loop converging, printing in alternating and superimposing positive and negative frames, further stylizing the features of the worker. Through all of this transformation, it must be said, Rimmer disintegrates the image as best he can, but he does not destroy it, he can’t destroy the image. Image is resilient. We glimpse the core resilience of this shot when Rimmer strips the composition down to its essential construction—the shape of a face with eye and mouth and nose holes in photo-negative high contrast, a form that is later coloured wildly, and takes on the crackling textures of magnified grain. The face, more than the action, remains: Rimmer’s operations drench the form in ambiguity, making a neutral countenance into the penetrating stare of a face without eyes. In the mystery of this figure, and of this face, we could glimpse almost anything.

And further to the announcement the other day about the impending release of my new book, Secret Museums: The Films of Arthur Lipsett, here is a trailer for the book! It’s available for pre-order now from Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Till next time!

Stephen Broomer // Art & Trash